|

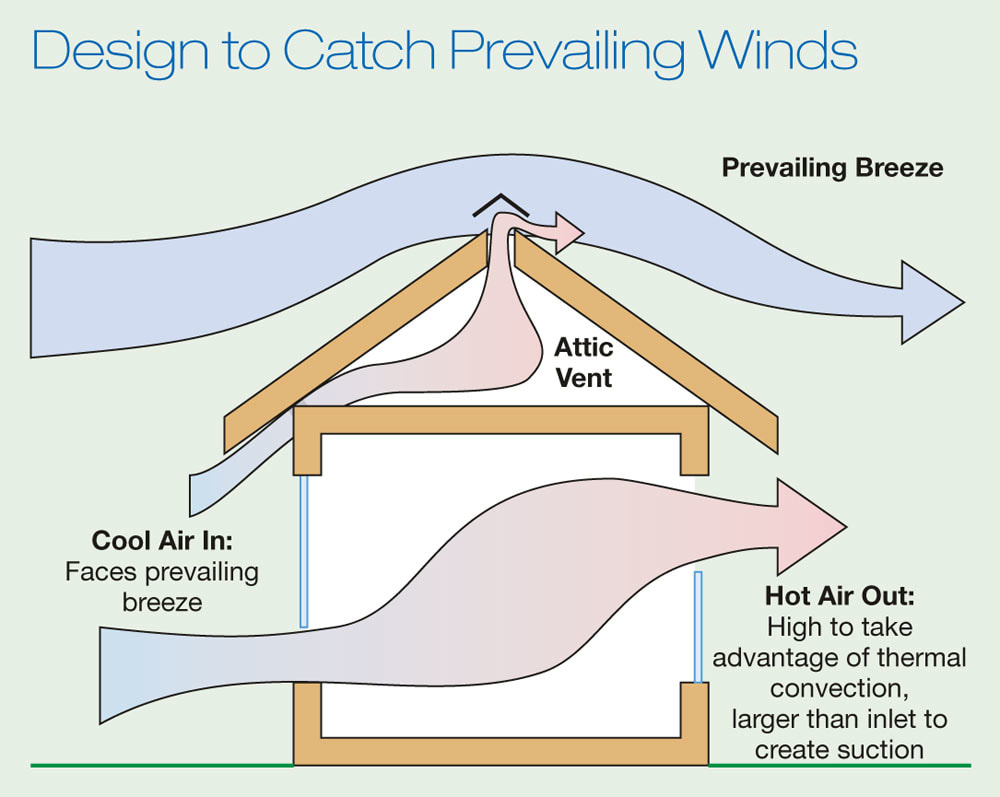

Written by Emily Udy, Preservation Manager At the heart of preservation is the desire to maintain the defining places of our community so that we can understand our place in the timeline of society. When we are engaged in preservation we are deciding what we want to survive into the next century, which is an awesome responsibility; one that belongs to us all. As we look from past to future it is imperative to address how preservation supports sustainability and resiliency. These three goals are intrinsically tied together, and in fact, the Preservation movement is indebted to the Sustainability movement for their efforts to preserve our natural environment. Salem, like any city settled on the seashore, has a history tied to the water, and as a result many of our historic resources will face natural demolition as flood levels change and average daily tides move higher. A Historic House is a Passive House Long before there was “preservation” or “sustainability” construction trends and materials evolved to meet the climate needs of their area. In New England many character giving features are not style preference but passive ways to keep a home comfortable. Historic buildings are oriented on streets taking advantage of prevailing winds. The small rooms in historic houses were easy to warm by closing the doors and keeping in the heat from the fire. Double hung windows allow air flow and stairways from basement to attic let heat vent upwards in the summer. Exterior and interior shutters on moderate sized windows each play a different role in protection from wind damage or keeping heat or cold in or out. Brick walls or thick plaster stay comfortable for longer when the temperatures change. The tree lined streets we associate with many historic neighborhoods add considerable cooling during summer months. Obviously, in modern times we can take advantage of these historic characteristics to keep our homes comfortable with less energy use. Inherently Sustainable Beyond historic construction methods, the preservation profession has long been contributing to environmental conservation whether it was recognized or not. Donovan Rypkema, a leading preservation economist, pointed out in a lecture that he delivered in Salem in 2015 that saving a 2200 sf house from demolition is equivalent to cutting the lifetime plastic bag use of 440 people. Rypkema also highlighted a study that showed that to rehab a historic house used 47 tons of material energy (that includes energy used to extract, create, ship and discard the materials). To build a new home on a clear site used 182 tons (3.5 times more) and to demo the old house, haul it to a landfill and rebuild with LEED gold architecture standards used 351 tons – more than 7 times more energy than would rehabbing a house of the same size. As stated by Stephanie Meeks, President of the National Trust – it simply does not make sense to recycle cans and newspapers to save energy and not recycle buildings. In Salem, so far we have only a few “tear-downs” a year, even in unprotected historic neighborhoods, but we must be vigilant; as the desirability of Salem’s neighborhoods increase so will pressure to build new. It is especially important to carefully evaluate the ideas that “it takes more money to rehab than to build new,” or that “new buildings are more energy efficient than old ones.” In many cases these are falsehoods that become even more outlandish when you consider the social and environmental costs of demolition. Preservation ensures that we aren’t throwing away our past and our future. A Traditional Neighborhood is a Walkable Neighborhood In Salem’s case, there are many areas in the heart of our city where demolition happened decades ago. There is much of traditional neighborhood development style that today’s developers can utilize, including methods that increase sustainability. Thoughtful re-development of urban parcels allows new construction to take advantage of a city that has been walkable for centuries. Walkability promotes individual health and well-being; community-wide it means less car trips, higher use of public transportation, less use of fossil fuels, lower parking needs, fewer fields of asphalt, smaller heat islands, better air quality and lower consumption of automobiles in general. If large-scale new construction in our city used a traditional style of city planning we would see fewer developments that were cut off from neighborhoods and rendered residents dependent on their cars. Traditional neighborhood construction will also extend the character and quality of life found in our historic neighborhoods to new city residents. It must be noted that proximity is not the same as walkability, specific design steps need to be taken to make leaving the car at home the default option. Build New to Last There is one final consideration about sustainability and new construction in our historic city that references the cliché “they don’t build things like they used to.” While material and labor supplies may be different than then were in the past, it is hard not to notice that in a city with centuries of quality construction some new buildings are built to last only a few decades. Institutions like the city government and community advocacy organizations must expect the best from our developers. Most importantly, the members of our community must demand high quality, lasting design and construction. Historic Salem’s intention when commenting on new construction is to ask that what is being built now will be worth preserving in 100 years, at a minimum. All of our efforts to cut plastic bag usage now will be for naught if we end up tearing down buildings that have outlived their usefulness before the builders have even retired.

I’m going to conclude with this statement from the National Park Service: Historic preservation is inherently a sustainable practice. A commonly quoted phrase, “the greenest building is the one that’s already built,” succinctly expresses the relationship between preservation and sustainability. The repair and retrofitting of existing and historic buildings is considered by many to be the ultimate recycling project… Further reading: National Park Service page on Sustainability, that I quoted above. The National Trust and their Preservation Green Lab have information from rehabbing historic windows to reusing industrial cities.

1 Comment

Nina Cohen

10/6/2017 12:23:42 pm

Wonderful piece connecting preservation and sustainability, Emily. Living a car-dependent life in Salem leads to frustration and stress. A switch to walking/biking or using transit brings unexpected pleasures like a recent joyous ride to Boston on the sunrise ferry.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

Follow us on Instagram! |

|

|

Historic Salem, Inc. | 9 North Street, Salem, MA 01970 | (978) 745-0799 | [email protected]

Founded in 1944, Historic Salem Inc. is dedicated to the preservation of historic buildings and sites. Copyright 2019 Historic Salem, Inc. - All Rights Reserved

|